When brewing mead (or beer, wine, cider, etc.) with a commercial strain of yeast, most homebrewers rehydrate the yeast before pitching it. Meaning, they activate the yeast with water and yeast nutrients before adding it to the must.

But for years, we've advocated just tossing the dry yeast on top of the batch (known as "direct pitching", and received a fair bit of flack for it.

So, do you need to rehydrate yeast before pitching? If so, why? If not, why not?

What if I don't want to read a long article and just want the damn answer?

Good for you! So many articles these days bury the lede for SEO purposes. This is not our style. The answer to the question at hand is: No. You do not need to rehydrate yeast before pitching.

There are a few circumstances where it might be beneficial (more on that below), but new research has come out saying that rehydrating yeast might actually be detrimental.

What is rehydrating yeast and why do people do it?

Rehydrating yeast is simply the practice of putting your dry yeast into water before you pitch it into the must or wort that you hope will ferment. It was believed that the shock of the sugar (or something like that) would scare and upset the poor little yeast and make it lazy or fail to fully attenuate (completely ferment).

The one situation where rehydrating is still recommended is for very high gravity fermentations where you're using a rehydration nutrient blend. In this case, however, we still prefer to direct pitch on a lower abv batch and build up a larger colony of happy, healthy yeast over time. This is what we do for our Ancient Collection.

Photo by Your Best Digs

Why should I believe an article on a meadmaking website over countless, heated arguments on forums across the Web?

We're a reliable source on the subjecting of rehydrating yeast for three reasons.

- Our livelihoods depend on a vigorous, consistent fermentation. Over ten years and hundreds of batches, we've taken rigorous notes (usually) and found many advantages to direct pitching yeast.

- The idea of rehydrating yeast has been controversial for years; it's not as if this is an overturning of the Second Law of Thermodynamics.

- The people that make the yeast (Lallemand) who used to advocate rehydrating just released this statement:

Recent R&D has shown that there is no significant difference in fermentation performance between dry-pitched and rehydrated yeast.

Dry pitching is the preferred method of inoculating wort. This method is simpler than rehydration and will give more consistent fermentation performance, also reducing the risk of contamination.

Rehydration of yeast prior to pitching should be used only when equipment does not easily facilitate dry pitching, for bottle conditioning, and for some fermentations other than beer.

Now, you may have noticed that last line and be thinking "mead" is "other than beer." This is true. "Good noticing!" as we would say to our two-year-old, but the conditions in a mead with sufficient nutrients from other ingredients or a high-quality yeast nutrient are very similar to beer. This is true for all of our Craft Meads, at the very least.

What are the risks if I want to keep rehydrating my yeast anyway?

Hmmm... Dunno. Probably pretty minimal. We've definitely done it. In 2021, we used a rehydrating nutrient alongside our regular nutrient for a while and saw no ill effects. The biggest risks, according to the Lallemand, is the risk of infection by adding an extra, unnecessary step and a possible decrease in viability if it's left for too long.

For us, it was the added time and cost with no tangible improvement in the final product.

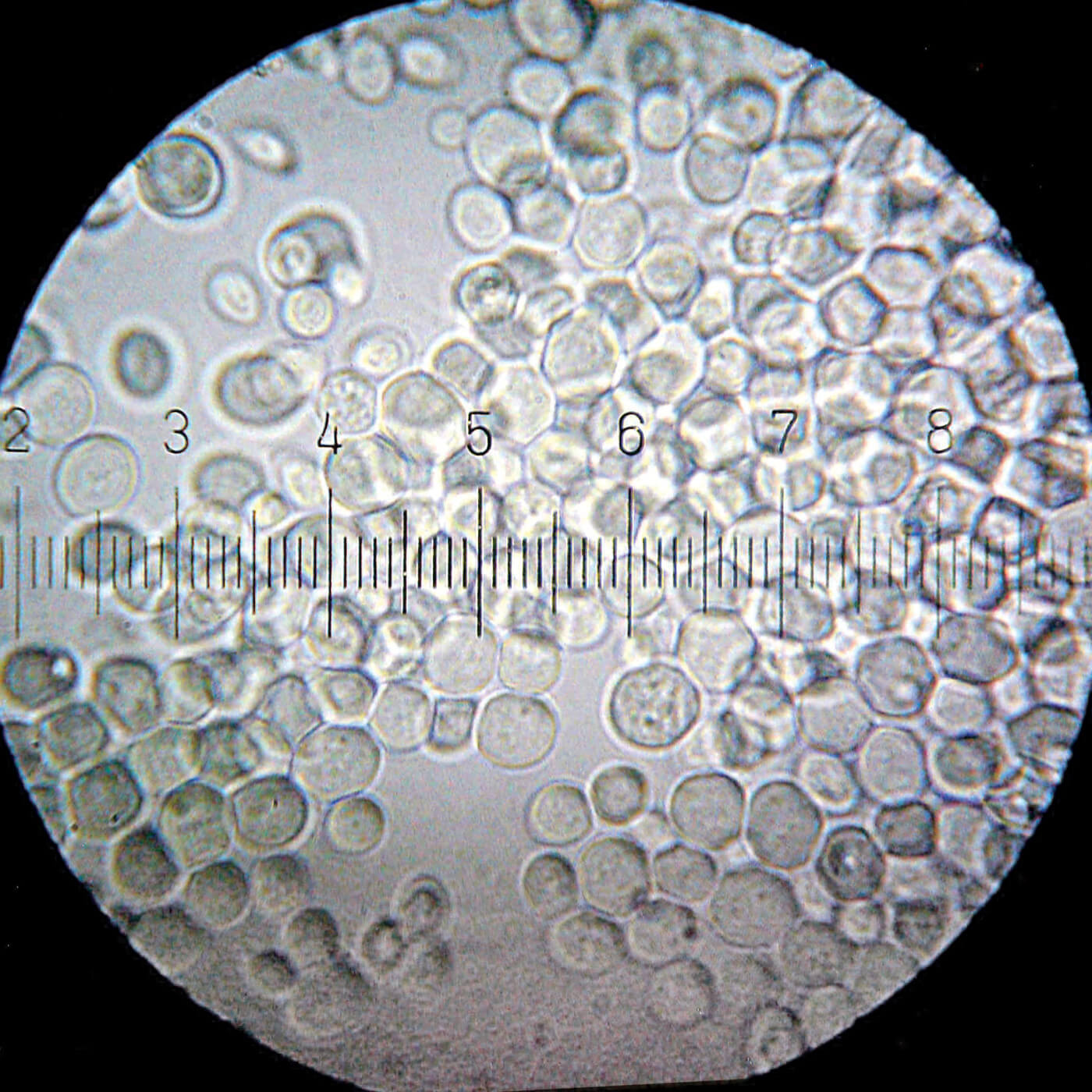

Photo by Bob Blaylock

In Conclusion

That's it, friends! Keep rehydrating the yeast if you want to (or have seen real, positive results). But if you think it's a hassle and you've been wanting to quit (or if you already have) let go of your guilt! Join us in being lazy brewers making fabulous mead!