When discussing shipping wine, mead, cider, or other beverages around the country, people inevitably worry about "bottle shock." In this article, we go through what bottle shock is, what it isn't, and what you can do about it.

What is bottle shock? (And is it even a real phenomenon?)

You'd think in an article covering the topic of bottle shock, we'd start off by telling you what it is and what causes it, but it's actually open to debate whether it's a real phenomenon at all!

While most consumers and many researchers agree that shipping wine through the mail causes a set of temporary changes to the product, this is by no means universally agreed upon. And, since this is a matter of relatively subjective taste, it's difficult to get empirical evidence that confirms or denies the claim.

That said, since the concept has the backing of many experts on oinology, we'll carry on with the article trusting to their judgment.

So, the technical definition of bottle shock (also called "bottle sickness") is a flavor and aroma in wine described as flaccid, flat, or muted. It occurs after the wine has been transported a great distance, jostled excessively, or immediately after packaging. This muted character goes away after the wine is allowed to rest.

Will this article have anything to do with the 2008 film of the same name?

No. You will need to head elsewhere for your trivia about Alan Rickman.

OK, one factoid: Alan Rickman turned down knighthood, but never gave a public reason as to why.

What is the proposed mechanism for bottle shock? (AKA What the heck causes it?)

Since there isn't a scientific definition for bottle shock, the mechanism is also up for debate. Outlets like Wine Enthusiast don't venture any conjectures on the cause, but they do insist that it's real and prescribe a treatment for it.

Others seem to believe that it's an overly rapid aeration of the wine as oxygen penetrates the cork faster than it would under sedentary circumstances. This might explain why bottle shock occurs during packaging, especially in a homebrew environment.

Unfortunately, one strike against this theory is that no one has noted a difference in bottle shock in air-tight packaging (plastic/metal screwtops or cans) versus traditional corks.

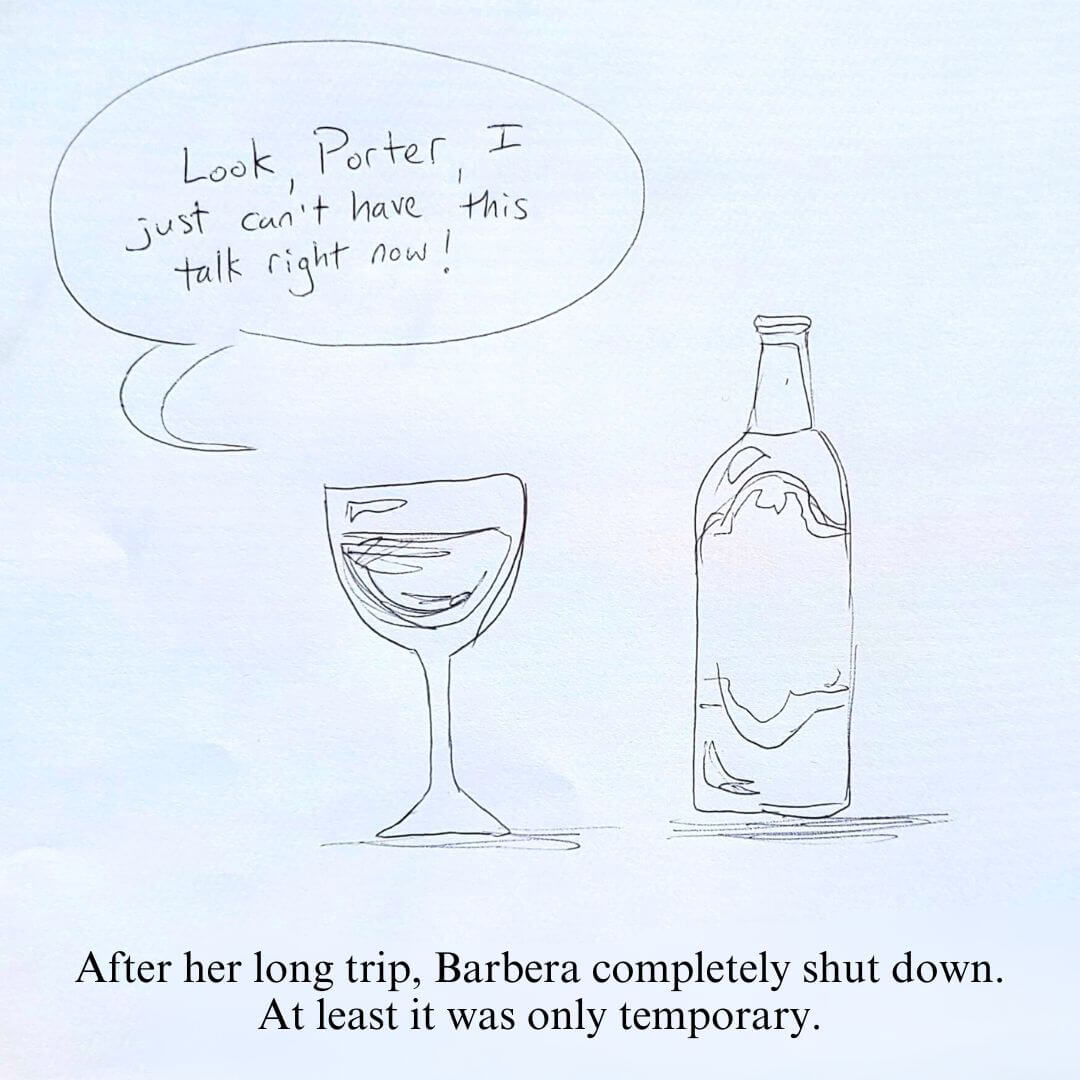

Our personal favorite theory comes from Signature Cellars with their enigmatic suggestion that:

The compounds, tannins, phenolics etc. which are the complex element in wines are continually evolving. This evolution happens with each other as well as on their own. Motion or heat can cause stress to this standard process resulting in the wine to shut down temporarily. [Full Article Here]

The good news about that theory, at least, is that it doesn't actually mean anything and is, thus, impossible to prove wrong and it inspired this absolutely incredible comic from our resident artist Autumn!

So what does cause bottle shock? Scientists are unwilling to propose a mechanism, and the rest of us are talking through our hats.

Do all beverages suffer from bottle shock?

There does seem to be some consensus here: Bottle shock is much more likely to occur in:

- Grape-based wines

- Still (i.e. non-carbonated) products

- Products in bottles rather than smaller packaging like cans

I've definitely noticed a difference in products that don't fit those categories. What's going on?

Ah! You've found the important question! Things other than bottle shock can happen to alcoholic beverages that go through the mail!

Many beers need to be held at refrigeration temperatures for their entire lifespan. Things with hops react poorly to high temperatures and will skunk if allowed to sit in the sun in any packaging other than cans, kegs, or dark brown bottles. (Despite the common misconception, light, not heat, causes skunking.)

Our meads are all temperature stabilized, which means that we use a natural process to bring them up to warm temperature, but since we don't filter, all of the yeast and sediment can get roused up changing the beverage pretty dramatically.

Luckily, for wine, mead, cider, and sake that got a little... disheveled from a transcontinental voyage, there's an easy solution! (Sorry beer, you have a refrigerated supply chain for a reason.)

How do you deal with bottle shock?

Time! Let it rest! Let it sit on your counter either upright (in the case of cider and our meads) or on its side for traditional red wines.

The process by which our mead comes back to its optimal form is well documented: the trub settles back out.

As for wine, well, since bottle shock is a mystery, so is the process by which it ummmm... recovers from shock?

For wines, it's recommended you wait for about two weeks. For all of our craft products, we recommend a day or two. For our Ancient Collection, the same usually applies. Since neither of them is suffering from bottle shock, rather just a jostling of the trub, it's really just to help it taste more like it does on draft.

A lot of folks actually roll our cans to get all of the hazy goodness, so right out of the mail, especially on a cool January afternoon, might be ideal!